Rattled, the Portuguese made amends by offering Rs3 lakh as compensation, but on the condition that the Mughals expel the English from Agra. Furthermore, the emperor “sealed up their church doors and hath given order that they shall no more use the exercise of their religion in these parts". As one observer noted, Jahangir immediately had Daman besieged, blocked all Portuguese trade in Surat, and “hath likewise taken order for the seizing of all Portingals (sic) and their goods within his kingdoms". The whole affair was meant to gain leverage at a time when the Portuguese were threatened by competition from other European companies. The action was unprecedented, and, given who the owner of the vessel was, the insult landed straight on the otherwise cheerful, opium-loving Jahangir. In 1613, however, the Portuguese decided it was a clever idea to seize and subsequently burn the Rahimi. In addition to goods worth millions, the dowager empress regularly conveyed Muslim pilgrims to Mecca on her ship-this, when she wasn’t actually funding the construction of mosques, even while she remained herself a practising Hindu. She was also the proprietor of the Rahimi, believed to be the largest Indian vessel trading in the Red Sea, displacing 1,500 tonnes, its mast some 44 yards high.

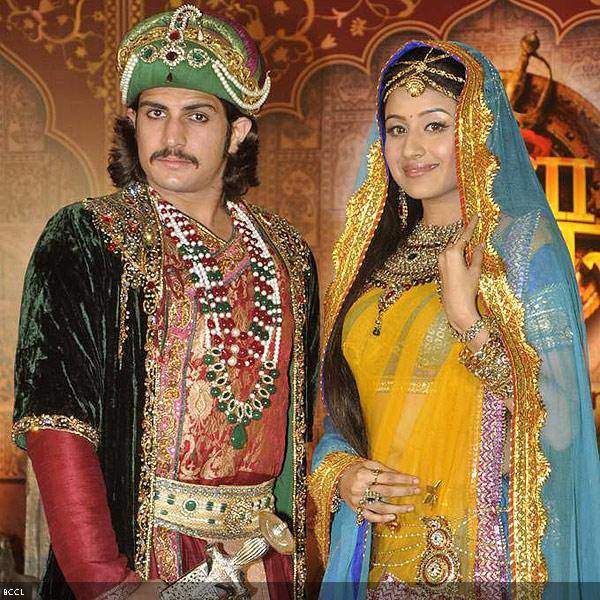

Findly notes, she was one of four seniormost figures and the only woman to hold a military rank of 12,000 cavalry, entitling her to the right to issue firmans of her own. Described by a contemporary as “a great adventurer", she towered over phenomenal business enterprises even while sequestered in the Mughal harem. While conventional depictions are somewhat limited-she is beautiful and regal in a tedious, overblown sense-in actual fact, the dowager was a formidable woman. The lady in question was Mariam uz-Zamani, though she is often popularly called Jodhabai, the Rajput princess who was Akbar’s wife and Jahangir’s mother.

JODHA AKBAR STORY FULL

In 1613, a Hindu lady also got embroiled in these Mughal-Portuguese dynamics, her wrath bringing down the full force of the empire, ringing the death knell of the latter’s long-standing power at sea. Then there were religious concerns: The Portuguese were such fervent Christians that each cartaz (licence) carried images of Jesus and Mary-a troubling detail for Muslims compelled to buy these documents in order to do the haj. Politically, the ignominy of seeking licences was a demonstration of the limits of Mughal power, always somewhat embarrassing when the emperor was officially “Conqueror of the World". But that September, Portuguese provocation was so brazen that only firm action could restore Mughal prestige. The emperor, to be sure, was a friendly, curious man-when the English presented him two mastiffs, he was so thrilled he had the dogs carried around in palanquins-and he might have allowed things to carry on as before. In 1613, during Jahangir’s reign, however, the Portuguese, already imperilled by the arrival of the Dutch and English, went a step too far, hastening their decline in India. Even as Akbar dismissed the Portuguese as “chickens", Mughal ships quietly paid to carry on their business-the Europeans might have been overpowered were they on land, but on international waters their mastery of naval warfare ensured that even the imperial family gnashed its teeth but, ultimately, fell in line. It was, instead, the writ of the king of Portugal that prevailed in the Arabian Sea, and without Portuguese permission, no princess, of whatever consequence, could depart India’s shores. It was, however, revealing that even a senior representative of the imperial harem found herself applying for leave to sail, for the truth was that the Mughal emperor’s power met its limit at the beach.

It was no surprise that the begum paid in town, not coin-Gulbadan was, after all, the daughter of emperor Babur and aunt to mighty Akbar, then sovereign of all of upper India. Negotiations dragged on, and eventually, she had to bribe with the entire city of Valsad in order to board her boat. In 1575, authorities in the port of Surat prevented a woman called Gulbadan Begum from embarking on her pilgrimage to Mecca for an entire year.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)